Dear Lieutenant Governor Will Ainsworth,

On the 29th of June of this year, 2023, you tweeted the following:

You’ve gone on record many times about the need for Alabama to widen this highway, even going so far as to recommend the leadership of our Department of Transportation should be replaced with people who favor such an expansion. Well, I happen to live in Montgomery, and I travel on I-65 frequently enough to have been ensnared in hours-long traffic jams many times. I have also been a student of transportation research for several years, and I can confidently say that widening I-65 is the wrong move for Alabama. These traffic jams are not the result of insufficient road capacity; they happen because there is no alternative to driving.

Highway expansion has been proven, time and time again, not only to not “fix” traffic, but to actually make it worse; even major mass-market publications like the New York Times and Bloomberg acknowledge this phenomenon. You might think that creating space for more cars by adding lanes would let drivers spread out and speed up, opening up the road and clearing traffic. In reality, though, as quickly as the existing cars spread out, new cars fill the gaps back in, because almost as fast as new capacity is created, demand for that capacity is also created.

Think of it this way. Let’s say you live in a neighborhood near Perry Hill Road, and Publix opens up a new store just off I-85 in Chantilly, 7 highway miles to the east. If ALDOT adds a lane to 85, suddenly your travel time from Perry Hill to Chantilly Parkway is shortened by a few minutes and you’ll probably take trips to Publix more often. Maybe you forget something on one trip, but since the store is so much quicker to get to, you can just go back and get it tomorrow. Nice, right?

Well here’s the problem. Several of the other folks in your neighborhood also shop at Publix, and are doing the exact same thing. Other folks, maybe in the neighborhoods nearby, have wanted to shop at Publix but didn’t or couldn’t, because it took too long to get there. Now that the highway is wider and the travel times are shorter, they can get there faster, and so they start shopping at Publix instead of wherever they were shopping before. Pretty soon, everyone in your neighborhood and the neighborhoods surrounding it are using that newly-widened highway to get to that one Publix–and it soon becomes just as slow and congested as it was before the lane was added.

An I-65 expansion would be similar. If the initial expansion shortens travel time from Birmingham and Montgomery to the beaches of Mobile and Gulf Shores, Birminghamians and Montgomerians will take trips to the beach more often, completely cancelling out the benefits of widening the highway in the first place. And this isn’t merely a hypothetical either, multiple studies across the globe have shown that “the initial benefits from congestion relief [e.g. road-widening] fade within a decade.” This is the principle of Induced Demand, and it means that road-widening projects are doomed from the start, wasting billions of taxpayer dollars with nothing to show for it. (Induced Demand does also affect trains and transit, but these modes are so much more space-efficient that its effect is easily absorbed or accommodated.)

I-65 also has an appalling fatality rate; the highway is Alabama’s deadliest, and is far-and-away the most crash-prone road in the state. The almost 36,000 reported crashes on I-65 since 1999 are nearly double the number of wrecks on the next-worst Interstate, I-59, and are over 25% more than the next most crash-prone road, Alabama State Route 1. And since an expansion would, as previously shown, not reduce traffic (in fact likely greatly increasing it over the current levels), and since the top two causes of accidents nationwide are distracted driving and speeding, both of which are very likely to happen on an hour-plus-long Interstate trip, a reasonable person must conclude that this expansion will ultimately cause more crashes, and more lives lost. Not to mention that many, if not most, of the traffic jams that Mr. Ainsworth uses as causus belli for expanding the highway are themselves caused by car accidents.

So instead of just building one more lane, what can we do?

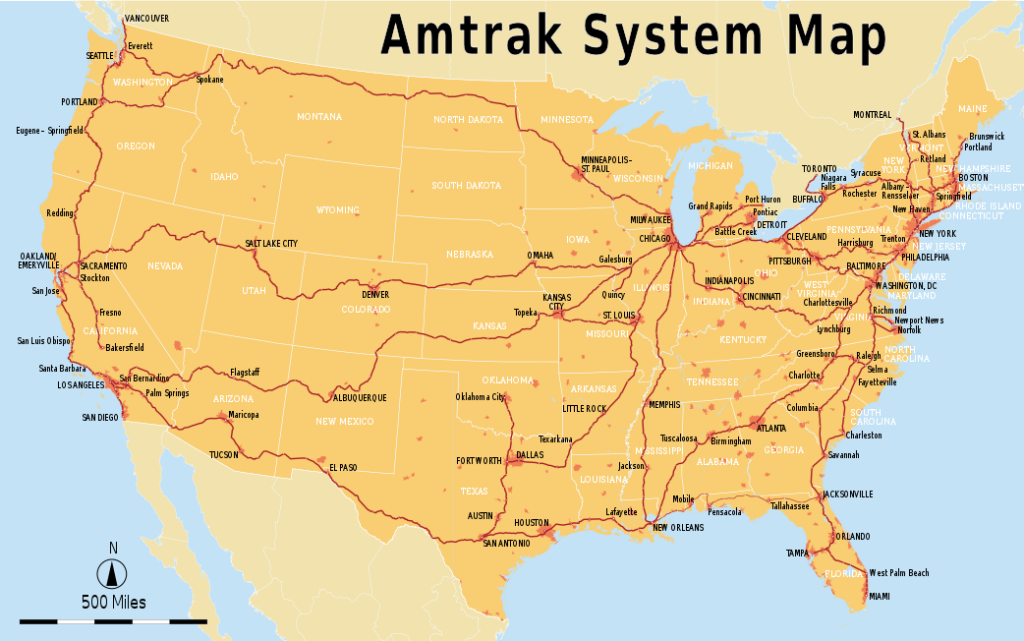

In a word, trains. Though there is currently only a single Amtrak train serving Alabama—the Crescent—which takes 3-and-a-half hours to make its once-daily trip paralleling I-20 through Anniston, Birmingham, and Tuscaloosa, I’m sure many Alabamians can remember a time when Alabama used to be a hub for passenger rail service, Birmingham most of all. At one time, over 50 passenger trains every day called on Birmingham’s Terminal Station, connecting the city to destinations like Chicago, Illinois; Miami, Florida; Memphis, Tennessee; Cincinnati, Ohio; Kansas City, Missouri; and even Portsmouth, Virginia; not to mention local services to just about every town of any consequence in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. And all this was during a time when Alabama had less than two-thirds of the population it has today. Since the creation of Amtrak in 1971, there have been a few attempts at running a train north-south through Alabama; the Floridian, a Chicago-Miami long-distance service, was cancelled in 1979 on account of deplorable track conditions—and thus on-time performance—north of Louisville, while in 1989, the Gulf Breeze—pictured above—made its debut as a section of the Crescent running between Birmingham and Mobile. The Gulf Breeze was itself cancelled after a mere 6 years, thanks to a cost-cutting initiative imposed by Amtrak’s budgetary constraints.

Two studies, available to the public on the Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs (ADECA) website, lay out plans for restoring a modified “New Gulf Breeze”service between Birmingham, Montgomery, and Mobile. The Phase I study, Birmingham to Montgomery, was prepared in 2014 by well-respected civil engineering firm HDR, with AECOM building upon it in the Phase II study—Montgomery to Mobile—published in January 2020. These studies lay out several options for establishing rail service, with highly detailed cost, revenue, and ridership estimates for each option. The studies conclude by ranking the options, and the top scorers—Birmingham-Montgomery Alternative 3 and Montgomery-Mobile Alternative 2b—generate the highest ridership for the lowest per-person cost, with 3 departures in each direction between Birmingham and Mobile, and an additional 6 trains each direction serving as regional commuter rail to the larger communities between Birmingham and Montgomery. At almost $1.7 billion dollars, the price tag attached to the project may seem high, but compared to the cost of widening I-65, the train is actually significantly cheaper.

But let’s compare the actual numbers. Using averages from conservative engineer Charles Marohn’s website Strongtowns.org, adding another lane in each direction to all 366 miles of I-65 in Alabama would cost $1.83 billion in taxpayer money, and the resurfacing all 6 lanes of asphalt highway—which must be done every 10-15 years for a state of good repair—would cost an additional $1 billion, thus bringing the total over 15 years to $2.83 billion. The up-front capital cost for the New Gulf Breeze is projected to be $1.663 billion, with an annual operating cost of $22 million, or $330 million over those same 15 years, meaning that the 15-year total cost for the train is $1.993 billion. Annualizing both those figures, the highway ends up costing Alabama about $189 million/year, while the New Gulf Breeze would cost $133 million/year. So we can clearly see that, just looking at the raw numbers, the train costs significantly less than widening the highway. But the cost comparison doesn’t take into account the fact that the train will generate its own revenue.

The ADECA studies estimate that at about $38 a ticket, the New Gulf Breeze will attract 232,800 annual riders, and thus will earn almost $9 million a year in fare revenue, and only from people actively riding the train. Unless Mr. Ainsworth intends to put tollbooths on I-65, the highway expansion will be paid for, in full, by all Alabama taxpayers, regardless of who drives where or who even drives at all. While both options would of course benefit all Alabamians, does it seem fair that folks in Andalusia, or Dothan, or Alex City should have to subsidize the full cost of Yankees being able to drive to the beach faster, when those Yankees could take a train that would not only be cheaper, but would also be paid for by the people who actually use it?

Now, in previous debates over passenger trains in Alabama, many of our leaders, including Governor Ivey, have said that the economic benefit of the passenger train is overshadowed by the cost of delaying the freight trains that use the existing infrastructure. The ADECA studies do put the New Gulf Breeze on existing CSX Transportation-owned tracks, and even though both alternatives provide generous improvements to track capacity, CSX may still worry about the impact on its freight trains. Allow me to put those fears to rest.

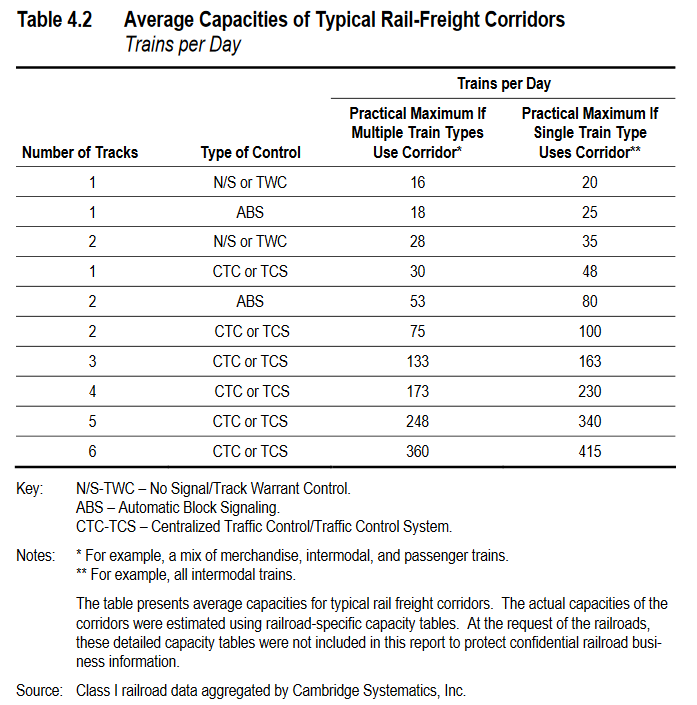

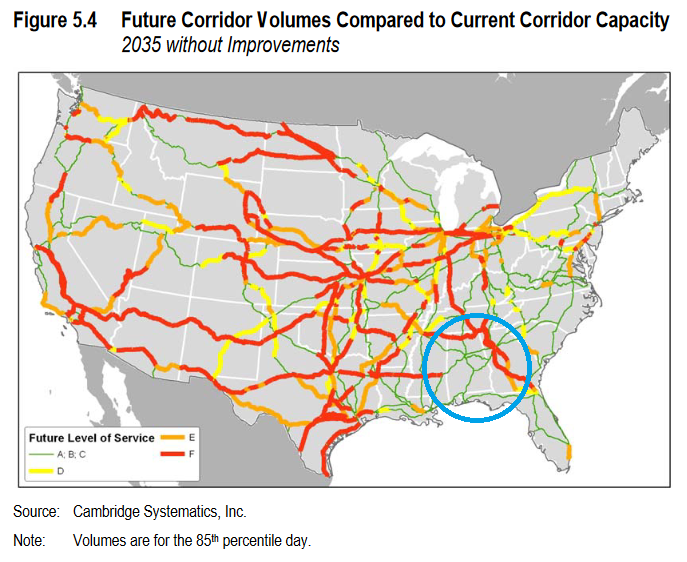

According to a 2007 Freight Rail Infrastructure Capacity Study, prepared for the freight rail lobbying group Association of American Railroads (AAR) by Cambridge Systematics, the maximum practical capacity for operating “mixed traffic” on a single-track railroad equipped with a Traffic Control System or TCS (also known as CTC), is about 30 trains per day. Adding a second TCS-equipped main track to the same corridor actually more than doubles practical capacity, enabling movement of about 75 trains per day in mixed traffic, which, according to the AAR study, includes “a mix of merchandise, intermodal, and passenger trains.” Including the New Gulf Breeze, these are almost exactly the types of traffic the line sees; the only omission of note is heavy bulk “unit trains,” which are much more flexibly scheduled and can thus be fairly easily slotting into an existing corridor’s flow of traffic. (Unit trains are also what I would call “route-agnostic,” meaning that they can easily take alternative routes that may be slower in order to relieve schedule pressure on a major corridor, similar to a leisure traveler leaving the Interstate for a two-lane U.S. Highway due to a major traffic jam.) The FRA study also analyzes which rail lines are expected to exceed their 2005 train capacity by 2035, using the U.S. DOT’s Freight Analysis Framework, a tool that is used to calculate national freight demand across all modes.

As the above image shows, almost every line in Alabama—circled in blue—is projected to be “below practical capacity” for the 85th percentile day in 2035. In other words, even on a busy day for freight traffic, there’s plenty of room for the 6 daily trains of the New Gulf Breeze between Birmingham and Mobile, and there’s likely even enough room to extend the train up to Decatur and Huntsville in the near future. All of the lines in question are TCS-equipped, and most are single track with generous sidings, with some sections of two or even three tracks, including a stretch of double-track spanning about 20 miles between Birmingham and Pelham. And just to be extra safe, the ADECA studies call for improvements to the existing infrastructure, including adding a third main track along that 20-mile stretch, to ensure that the corridor will remain fluid. And as a reminder, this is included in that $1.663B total project cost!

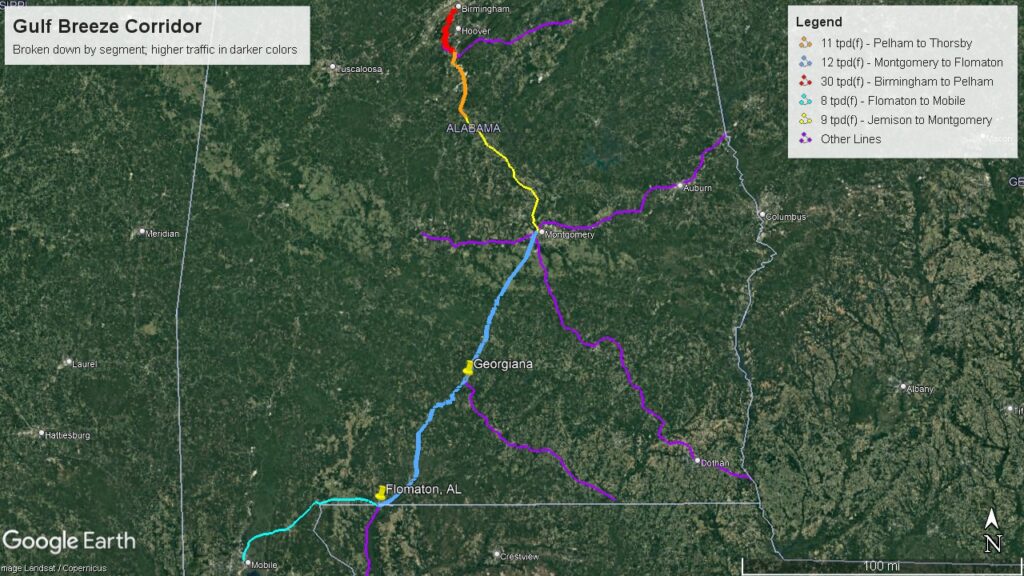

Freight operations have changed since the AAR study was published, though, most importantly CSX’s 2017 implementation of the “Precision Scheduled Railroading,” or “PSR,” operating philosophy. Entire books could be written on what PSR is and what it does, but its main affect on the New Gulf Breeze is that the number of freight trains being run has actually decreased, but those trains have become much longer, often stretching over 2 miles. The ADECA studies do address this issue somewhat—the Phase II study having been published well after PSR’s implementation—stating that freight traffic between Montgomery and Mobile consists of an average of 14 trains, and traffic between Birmingham and Montgomery varies between 11 and 35 trains, in a 24-hour period. So, since I studied rail capacity at the University of Illinois, and having earned my Federal Railroad Administration’s 242.207 Conductor Certification on a railroad that operates passenger, general freight, and bulk trains together on a single-track corridor, I decided to check the data myself.

According to publicly-available data tables, accompanied by personal observation over the course of several months, I found that CSX operates 54 scheduled freight trains—trains that would incur penalties by being delayed—on all segments of track between the Birmingham and Mobile Amtrak stations. When I broke down the list of 54 freight trains by segment, I found that only two trains used the corridor in its entirety. Here’s the breakdown:

- 30 of the 54 scheduled freights on the corridor use the 21 miles between Birmingham and Pelham, Alabama. 20 of these take the purple line on the above map, which splits at Pelham for Atlanta and points in Florida. The ADECA Phase I study recommends adding an additional third main on this section, as it is the busiest portion of the line.

- 8 of the remaining 24 freights cross over the corridor in Montgomery, on one of the various other lines CSX owns. They would interact with the corridor only on the short section of double-track CTC in Montgomery alongside Union Station, and thus I have not included them in the total train counts on the above map. The ADECA studies also recommend adding an additional track here for yard movements.

- 3 more trains are local freights to points west and south of Mobile, and thus would only interact with the passenger trains on the short stretch of double track between CSX’s freight yard and the Convention Center station. I’ve left these locals out of the above map also, due to their low impact.

This leaves 23 trains operating significant distances on the single-track mainline of the corridor, but of those 23, only two use the entire line between Birmingham and Mobile: - 15 daily freight trains are scheduled between Montgomery and Birmingham, 4 of which are “local” trains that operate out of Calera. 3 of those “locals” run on weekdays only, and one simply shuttles cars to Birmingham and back.

- 14 trains use the line between Mobile and Montgomery, but not all of it. 2 trains from each end of this segment split from the corridor at Flomaton, Alabama, leaving only 12 “unique” trains that the passenger trains would have to contend with. And of those 12, 6 are locals, with 2 of those running on weekdays only.

Here’s a table of all those trains, where they go to and come from, and what CSX calls them (their “symbol”):

| Index | Symbol | Origin | Destination | Frequency | Notes | Direction | Location | Extent of Impact |

| Lineville Sub/S&NA North Trains: | ||||||||

| 1 | I025 | Bedford Park, IL | Moncrief Yard – Jacksonville, FL | Daily | Priority Intermodal | SB | Birmingham | Boyles Yard to Pelham (Lineville Sub) |

| 2 | I026 | Duval Yard – Jacksonville, FL | Bedford Park, IL | Daily | Priority Intermodal | NB | Birmingham | Pelham to Boyles Yard (Lineville Sub) |

| 3 | I028 | Fairburn, GA | Bedford Park, IL | Daily | Priority Intermodal | NB | Birmingham | Pelham to Boyles Yard (Lineville Sub) |

| 4 | I029 | Bedford Park, IL | Fairburn, GA | Daily | Priority Intermodal | SB | Birmingham | Boyles Yard to Pelham (Lineville Sub) |

| 5 | I125 | Pigeon Park – Memphis, TN | Southover Yard – East Savannah, GA | Daily | Intermodal | SB | Birmingham | Boyles Yard to Pelham (Lineville Sub) |

| 6 | I126 | Southover Yard – East Savannah, GA | Pigeon Park – Memphis, TN | Daily | Intermodal | NB | Birmingham | Pelham to Boyles Yard (Lineville Sub) |

| 7 | I140 | Fairburn, GA | NWO ICTF – North Baltimore, OH | Daily | Mani-Modal | NB | Birmingham | Pelham to Boyles Yard (Lineville Sub) |

| 8 | I141 | NWO ICTF – North Baltimore, OH | Fairburn, GA | Daily | Intermodal | SB | Birmingham | Boyles Yard to Pelham (Lineville Sub) |

| 9 | M221 | Boyles Yard – Birmingham, AL | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Daily | Via Manchester | SB | Birmingham | Boyles Yard to Pelham (Lineville Sub) |

| 10 | M514 | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Radnor Yard – Nashville, TN | Daily | Mani-Modal | NB | Birmingham | Pelham to Boyles Yard (Lineville Sub) |

| 11 | M515 | Radnor Yard – Nashville, TN | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Daily | Reroute Manifest | SB | Birmingham | Runs Lineville Sub as reroute |

| 12 | M518 | Boyles Yard – Birmingham, AL | Radnor Yard – Nashville, TN | Daily | Manifest | NB | Birmingham | north end of Boyles Yard |

| 13 | M647 | Clearing Yard – Chicago, IL (BRC) | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Daily | Manifest | SB | Birmingham | Boyles Yard to Pelham (Lineville Sub) |

| 14 | M648 | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Clearing Yard – Chicago, IL (BRC) | Daily | Reroute Manifest | NB | Birmingham | Runs Lineville Sub as reroute |

| 15 | L681 | Ensley, AL | Ensley, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Birmingham | none | |

| 16 | L682 | Birmingham, AL | Phoenixville, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Birmingham | none | |

| 17 | L689 | Bessemer, AL | Birmingham, AL | Daily | Intermodal Turn | Turn | Birmingham | none |

| 18 | L803 | Birmingham, AL | Talladega, AL | As Needed | Turn | Birmingham | Boyles Yard to Pelham (Lineville Sub) | |

| 19 | L804 | Birmingham, AL | Talladega, AL | Sun, Mon, Thu, Fri | Turn | Birmingham | Boyles Yard to Pelham (Lineville Sub) | |

| 20 | L805 | Birmingham, AL | Talladega, AL | Tues-Sat | Turn | Birmingham | Boyles Yard to Pelham (Lineville Sub) | |

| Montgomery yard (A&WP/Dothan Sub) Trains: | ||||||||

| 1 | M526 | Montgomery, AL | Howell Yard – Atlanta, GA | Daily | Works Fairburn, GA | NB | Montgomery | originates in Montgomery yard; takes A&WP Sub |

| 2 | M527 | Howell Yard – Atlanta, GA | Montgomery, AL | Daily | Works Fairburn, GA | SB | Montgomery | terminates in Montgomery yard; takes A&WP Sub |

| 3 | M649 | Montgomery, AL | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Daily | SB | Montgomery | originates in Montgomery yard; takes Dothan Sub | |

| 4 | M650 | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Montgomery, AL | Daily | NB | Montgomery | terminates in Montgomery yard; takes Dothan Sub | |

| 5 | L676 | Montgomery, AL | Burkeville, AL | Sun-Thru | Turn | Montgomery | ||

| 6 | L697 | Montgomery, AL | Dothan, AL | Daily | SB | Montgomery | originates in Montgomery yard; takes Dothan Sub | |

| 7 | L698 | Dothan, AL | Montgomery, AL | Daily | NB | Montgomery | terminates in Montgomery yard; takes Dothan Sub | |

| 8 | L708 | Montgomery, AL | Chehaw, AL | M-Thus | Turn | Montgomery | originates in Montgomery yard; takes A&WP Sub | |

| Montgomery to Birmingham (S&NA South) Trains: | ||||||||

| 1 | M202 | Baldwin, FL | Osborne Yard – Louisville, KY | Daily | Reroute Autoracks | NB | Montgomery to Birmingham | Runs S&NA South Sub as reroute |

| 2 | M203 | Osborne Yard – Louisville, KY | Baldwin, FL | Daily | Reroute Autoracks | SB | Birmingham to Montgomery | Runs S&NA South Sub normally |

| 3 | M222 | Taft, FL | Osborne Yard – Louisville, KY* | Daily | Reroute Autoracks | NB | Montgomery to Birmingham | Runs S&NA South Sub as reroute |

| 4 | M520 | Gentilly Yard – New Orleans, LA | Boyles Yard – Birmingham, AL | Daily | Works Montgomery, AL | NB | Mobile to Birmingham | Runs S&NA South Sub normally; works Montgomery |

| 5 | M521 | Radnor Yard – Nashville, TN | Gentilly Yard – New Orleans, LA | Daily | Manifest | SB | Birmingham to Mobile | Runs S&NA South Sub normally; works Montgomery |

| 6 | M523 | Radnor Yard – Nashville, TN | Goulding Yard – Pensacola, FL | Daily | Manifest | SB | Birmingham to Flomaton | Runs S&NA South Sub normally; works Montgomery |

| 7 | M524 | Goulding Yard – Pensacola, FL | Radnor Yard – Nashville, TN | Daily | Manifest | NB | Flomaton to Birmingham | Runs S&NA South Sub normally; works Montgomery |

| 8 | M645 | Boyles Yard – Birmingham, AL | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Daily | Via Thomasville | SB | Birmingham to Montgomery | Runs S&NA South Sub normally |

| 9 | M646 | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Boyles Yard – Birmingham, AL | Daily | Via Thomasville | NB | Montgomery to Birmingham | Runs S&NA South Sub normally |

| 10 | L677 | Calera, AL | Coosada, AL | Daily | Turn | Turn | Runs a portion of the S&NA South Sub normally | |

| 11 | L678 | Calera, AL | Thorby, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Turn | Runs a portion of the S&NA South Sub normally | |

| 12 | L679 | Calera, AL | Birmingham, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Turn | Runs a portion of the S&NA South Sub normally | |

| 13 | L680 | Calera, AL | Helena, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Turn | Runs a portion of the S&NA South Sub normally | |

| Montgomery to Mobile (M&M) Trains: | ||||||||

| 1 | M520 | Gentilly Yard – New Orleans, LA | Boyles Yard – Birmingham, AL | Daily | Works Montgomery, AL | NB | Mobile to Birmingham | Runs M&M Sub to S&NA South Sub; works Montgomery |

| 2 | M521 | Radnor Yard – Nashville, TN | Gentilly Yard – New Orleans, LA | Daily | Manifest | SB | Birmingham to Mobile | Runs S&NA South Sub to M&M Sub; works Montgomery |

| 3 | M523 | Radnor Yard – Nashville, TN | Goulding Yard – Pensacola, FL | Daily | Manifest | SB | Birmingham to Flomaton | Runs S&NA South Sub to M&M Sub; works Montgomery |

| 4 | M524 | Goulding Yard – Pensacola, FL | Radnor Yard – Nashville, TN | Daily | Manifest | NB | Flomaton to Birmingham | Runs M&M Sub to S&NA South Sub; works Montgomery |

| 5 | M601 | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Gentilly Yard – New Orleans, LA | Daily | Works Sibert Yard – Mobile, AL | SB | Montgomery to Mobile | Runs A&WP Sub to M&M Sub |

| 6 | M602 | Gentilly Yard – New Orleans, LA (UP) | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Daily | Works Sibert Yard – Mobile, AL UP MLIWX | NB | Mobile to Montgomery | Runs M&M Sub to A&WP Sub |

| 7 | M605 | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Gentilly Yard – New Orleans, LA (UP) | Daily | UP MCXLI | SB | Montgomery to Mobile | Runs A&WP Sub to M&M Sub |

| 8 | M606 | Gentilly Yard – New Orleans, LA | Rice Yard – Waycross, GA | Daily | NB | Mobile to Montgomery | Runs M&M Sub to A&WP Sub | |

| 9 | L670 | Montgomery, AL | Greenville, AL | Daily | Turn | Runs a portion of the M&M Sub | ||

| 10 | L671 | Georgiana, AL | Castleberry, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Runs a portion of the M&M Sub | ||

| 11 | L672 | Flomaton, AL | Brewton, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Runs a portion of the M&M Sub | ||

| 12 | L673 | Flomaton, AL | Evergreen, AL | Daily | Turn | Runs a portion of the M&M Sub | ||

| 13 | L674 | Pensacola, FL | Mobile, AL | Daily | NB | Runs a portion of the M&M Sub | ||

| 14 | L675 | Mobile, AL | Pensacola, FL | Daily | SB | Runs a portion of the M&M Sub | ||

| 15 | L685 | Mobile, AL | Theodore, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Mobile | none | |

| 16 | L687 | Pascagoula, MS | Mobile, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Mobile | none | |

| 17 | L688 | Mobile, AL | Theodore, AL | Mon-Fri | Turn | Mobile | none |

Altogether, then, the 6 new daily passenger trains recommended by the ADECA studies would have to share any given section of track with, at most, 12 scheduled freights a day–on a line that can comfortably handle 30 over its entire length. And while yes, bulk trains are a factor–particularly coal trains to the Port of Mobile–bulk trains can wait much longer for passenger trains to clear the line, and I never counted more than 6 such trains in a day. Combined with the 6 daily departures of the new Gulf Breeze, then, the line could see up to 27 trains per day, a figure comfortably below the figure published by the AAR report. And again, the capital cost estimates in both ADECA studies account for dramatic capital improvements over the line, including adding additional main tracks at choke points, extending sidings, and smoothing out curves to increase train speeds. CSX has in fact done some of this work themselves, in order to accommodate the longer freights brought about by PSR and building new connecting tracks to allow for more flexible routing.

The plans laid out for adding passenger trains would continue this trend of improvement for both passenger and freight trains. Faster track speeds, needed for competitive passenger service, mean quicker turnaround times for freight crews and locomotives too, not to mention better on-time performance for rail customers and better utilization of equipment overall. In fact, in a paper published by the University of Illinois’ RailTEC research center—for which I performed much of the operations simulation—found that, in general, “increasing schedule flexibility produced increases in average train delay” across a given network. In other words, if CSX makes sure the Gulf Breeze runs on time, and schedules their freight trains around it, then CSX freight trains will be more run on time too. And the enhancements CSX has already made mean that the capital costs for starting passenger service could be even less than the studies’ estimate–a figure which, again, is 10% cheaper than the cost of widening I-65.

Not only is the rail system cheaper in absolute terms, it also pays handsomely in external benefits. As a public comment on the Montgomery-Mobile rail study says, “one of the stated reasons for Amazon’s selection of New York and Washington was the existing transportation infrastructure” that those cities could offer. If Alabama wants to remain competitive for business, we can’t continue to rely on tax incentives and cheap labor.We need better infrastructure, and rail is the best option; for every $1 invested in rail service, $4 of economic development is generated, meaning that the $1.7 billion cost of the train would produce over $6.6 billion in economic activity. That’s about 2.4% of our state’s GDP, all in new business, thanks to the train. Alabama is also one of only three states that does not fund public transportation at the state level; the Public Transportation Trust Fund was created to in 2018 to remedy that, but it remains empty; state funding for Amtrak service between Birmingham and Mobile can change that in a big way, while also making Alabama’s transportation network far more equitable, accessible, and environmentally friendly. Meanwhile, sitting in traffic costs Alabamians an average of $2.1 billion annually, a figure which will continue to grow alongside Alabama’s population. I haven’t even begun to talk about the steady, well-paying jobs the train would create, or the increase in property values around every new station that gets built, or the lower stress and higher comfort a train can offer over a car or an airplane.

In summation, Lt. Gov. Ainsworth, I urge you to consider expanding rail service. It is becoming readily apparent that rail is the only viable, forward-looking solution to transportation in Alabama, and more broadly in America as a whole. Alabamians do not want our hard-earned tax dollars wasted on yet another highway expansion that will not only not relieve traffic, but will cost more than a rail-based alternative. In fact 60% of people surveyed by the ADECA studies said they would use rail service between Montgomery and Birmingham if it was offered; 90% said the same for Montgomery to Mobile. It’s clear that Alabamians want transportation that costs the taxpayers less, improves our economy and our environment, and brings us closer together, and that means expanding our passenger rail network. We want this train. Will you insist on staying trapped in the traffic jams of the past? Or will you get Alabama onto the right track for the future, and bring back the Gulf Breeze? I sincerely hope you choose the latter.

Sincerely,

A Concerned Citizen and Transportation Advocate

Revised July 28, 2023